Introduction

We live in the era of information overload, we consume massive amounts of information from different sources in a daily basis, but how do we find interesting stuff inside these information? How do we discover an interesting book out of the millions of books available in Amazon? How do we chose a nice pair of shoes out of the hundreds of thousands in Zalando? An interesting book for me might be a boring book for you, and a particular pair of shoes that is cool for me might be not your taste. Recommender Systems deal with problems like that, such a system uses previous purchases and user interaction to prescribe the user with items that most likely she would like to consume.

The core problem of recommender systems is to estimate a utility function that would predict how much a user would like an item, such a function takes into consideration previous purchases, user-site interaction, user-user interaction, item similarity based on their content, the context of a specific user session and other attributes.

Collaborative filtering

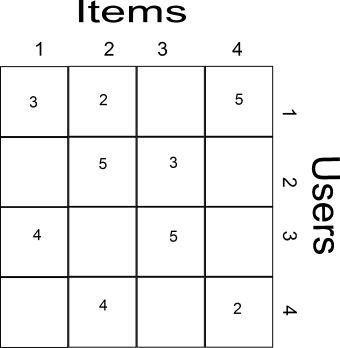

A popular algorithm that uses only previous purchases/behavior is collaborative filtering. On the collaborative filtering setting we have n user, m items and r ratings, those ratings can be collected either explicitly (e.g. stars in Amazon) or implicitly from user behavior (e.g. purchasing an item is better rating than putting it on the wish list which is better than just clicking the item without further actions). This kind of information is represented in a user-item matrix similar to the following example :

This matrix is a sparse matrix because not all users had rated all items. The aim of a recommender system is to fill this matrix. In collaborative filtering the items are modeled as vectors of the user ratings, therefore by using a similarity measure (e.g. cosine similarity) we can compute how similar are two items. A predicted rating is the weighted similarity of a user with an item (we give more emphasis on items that were more likable to the corresponding user). In the above example we have ,

,

,

by using cosine similarity we get

,

,

and so on. We compute the rating that

would give to

as

. On a similar way we fill the missing ratings and we recommend the highest rated items to the users.

The advantage is collaborative filtering is that it does not require a lot of domain knowledge and content extraction. On the other hand, requires a lot of ratings beforehand in order to perform well, because it suffers a lot of sparsity. Imagine having an inventory of millions of items, then the chances that items got rated from same users are very low. A way to overcome this problem is to use latent factors instead of the items in order to make recommendations, we can think of those latent factors as topics, e.g. for movies we would have Comedy, Horror, Romance, and others. These topics could reduce the dimensionality of our problem from millions of items to hundreds of factors and therefore suffer less from sparsity.

Model-based collaborative filtering

Model-based collaborative filtering (AKA supervised matrix factorization) is a way to learn the latent topics from the ratings given by users. As before, we have a triplets of user rated item with a particular rating , lets assume that we could decompose the rating into inner product of latent factors for the corresponding user and item:

and

are the k-dimensional latent features of user

and item

. All the user factors together are represented as a

matrix

, while the item factors are represented as a

matrix

. Multiplying both we get the reconstructed ratings matrix

. Our goal is too learn those latent factors by minimizing the following regularized loss:

S is the set of the known ratings. The regularization term helps us to avoid overfitting. The above objective function is a non-convex one. In order to solve such a minimization problem, we follow the alternating least squares principle, i.e. we fix the one set of parameters, minimize the with respect to the other (this makes the objective function a convex one), then we fix the other set of parameters and minimize with respect to the first ones, we iterate until the objective function does not decrease any more. Additionally, we can use stochastic gradient descent to speed-up the minimization of the above objective function. In such a case, we iterate over our ratings , we update

and

by following the corresponding gradient descent direction:

Where is the learning rate of our stochastic gradient descent updates. In summary, we initialize

and

with random values, we iterate over our ratings, we hold

stable and update for

and vice-versa by using the above update rules, and we finish when the objective does not decrease any further.

Model-based collaborative filtering and related methods are one of the most popular approaches to recommendations but their main disadvantage is the cold start problem meaning that when a new user we cannot recommend him anything, and a new item will never be recommended. In order to overcome such a problem collaborative filtering is often hybridized with approaches such as content based recommendations or popularity (e.g. “blockbuster”) recommendations for new items and users.